- Past performances

- It depends on the number of monkeys.

- The hot hand fallacy

- Alternative histories

- Russian Roulette

- An Even More Vicious Roulette

How well do you understand uncertainty and probability? How much do you think the rare events or the events that didn’t happen affect our lives?

In this article, I will argue about the role of sample spaces and what didn’t happen in daily life. How ignorance of alternative histories (we’ll see what these are) leads us to false conclusions. We’ll note that we understand very little about the role of randomness in life. We usually do not respond to probability, but to society’s assessment of it.

I want to make it clear from the beginning that although luck plays a huge role in almost all aspects of your life, what I ultimately propose is that “it is more random than most of us think” and not that “it’s all random.” Of course, skill counts. What your parents taught you about hard work and perseverance is true. Still, they do count less in highly random environments than they do in, say, dentistry.

Past performances

Can you judge the success of someone by their raw performance and their previous results? Sometimes, but not always. Take, for example, a trader. He lives in suburban New York, works in a private firm on Wall Street, and trades options. Say he makes money off every option he traded in the past month, the past year, or even the past two years. Does this make him less prone to the randomness of the market? Does this make him “wiser” about the movement of the market? Will you give him all your life’s savings based on his performance in the last five years? In fact, how much of his performance you must examine to be able to trust him.

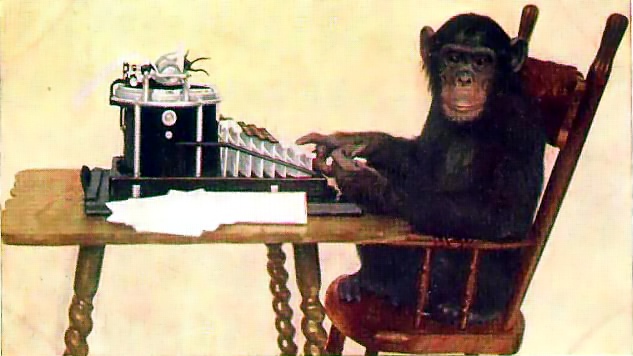

More than a hundred years ago, few statisticians proposed an interesting idea that is known as the infinite monkey theorem: If one puts an infinite number of monkeys in front of (strongly built) typewriters and let them clap away, there is a certainty that one of them would write an exact version of the Paradise Lost. Upon the first examination, this may seem less attractive a concept because one can argue that such a probability is ridiculously low. But let me carry the reasoning one step beyond. Now that we have found that hero among our sample of monkeys, would any reader invest your life’s savings on a bet that the monkey would write the Paradise regained next?

In this thought experiment, the less talked about and more interesting is the second step. How much can someone’s past performance (here, the typing of Paradise Lost) be relevant in forecasting future performance? The same applies to any decision based on past performance. Merely relying on the attributes of the past time series is not enough. Think about the monkey showing up at your door with his impressive past performance. Hey sir, I am the monkey who wrote the Iliad. Would you like to bet that I can introduce myself?

The problem with inference is generally more prominent with those whose profession is to derive conclusions from data. They often fall into this trap faster and more confidently than others. The more data we have, the more likely we are to drown in it. Common wisdom among people with a budding knowledge of probability laws is to base their decision-making on the following principle: It is improbable for someone to perform considerably well in a consistent fashion without his doing something right. This makes track records preeminent. People call on the rule of likelihood on a successful run and convince themselves that if someone performed better than the rest in the past, then there is an excellent chance of his performing better than the crowd in the future—and a very great one at that. But, as usual, beware the middlebrow: A little knowledge of probability can lead to worse results than no knowledge at all.

It depends on the number of monkeys.

I do not deny that if someone performed better than the crowd in the past, there is a presumption of his ability to do better in the future. But the sentiment might be weak, very weak, to the point of being useless in decision making. Why? Because the game depends on two factors: The randomness of the profession in question and the number of monkeys operating in the environment

The initial sample size matters greatly. If there are five monkeys in the game, I would be rather impressed with the Iliad writer, to the point of giving him all my money and retiring to Haiti with a now constant source of income. If there are a billion to the power of one billion monkeys, I would be less impressed. As a matter of fact, I would be surprised if one of them did not get some well-known piece of work, just by luck.

This problem enters the business world more viciously than other walks of life, owing to the high dependence on randomness (we have already belabored the contrast between randomness-dependent business with dentistry). The greater the number of people in business, the greater the likelihood of one of them performing outstandingly.

|

|---|

| Yo! I wrote the Iliad. What have you done, pesky human ? |

The hot hand fallacy

Now that we understand that the trader has less to do with his past success than he thinks he does. But is it possible for him to realize this and act accordingly? He will act as if he deserved the money. His continuous streak of success will inject him with so much serotonin that he will even fool himself about his ability to outperform the markets. Our hormonal systems do not understand whether this success of yours depended on hard work or a random fluke.

Often an increase in personal performance (whether it’s because of one’s hard work or by the grace of Lady Fortuna) causes a rise of serotonin in the subject, promoting the false belief in one’s actual ability. One is said to have “hot hands” or to be “on a roll.” Randomness is often ruled out as a factor until it takes a U-turn and the vicious downward cycle begins.

Many conning ideas originate from these discussions. A classical one is “The Mysterious Letter.” A con artist with the intentions of making money off of dubious investments from traders will mail you on January 1 to inform you that the market will go up during the month. It proves true, but you disregard it due to the well-known January effect (stocks have gone up historically during January). Then you receive another one on February 1 telling you that the market will go down. Again, it proves to be true. Then you get another letter on March 1, same story. By July, you are intrigued by the prescience of this mystery man. You “believe” in him. Based on this letter’s prediction, you are so sure to invest in a special offshore fund that you pour all your money into it. Two months later, your money is gone.

What did the con artist do? The trick is as follows. The con operator makes a list of 10,000 names out of a phone book. He mails a bullish (that the market will go up) letter to one half of the sample and a bearish (the market will go down) one to the other half. Next month he separates the names of the persons to whom he mailed the letter whose prediction turned out to be correct, that is, 5,000 names. The following month he does the same with the remaining 2,500 names until the list narrows down to 500 people. Of these, there will be 200 victims. An investment in a few thousand dollars worth of postage stamps will turn into several million.

See, the game highly depends on the sample size. This is the other aspect of the monkey’s problem; the other monkeys are not countable in real life, let alone visible. They are hidden away, as one only sees the winners—it is natural for those who failed to vanish completely. A typical example in colleges across India is that of “WebD.” As the number of monkeys (pardon my use of lineage) trying to make a webpage increases, one of them is bound to land a huge package or get selected in GSoC for 3 years straight. This doesn’t make you a bad developer; it’s just that he was the lucky monkey. Accordingly, one sees the survivors, and only the survivors, which imparts such a mistaken perception of the odds.

Alternative histories

I have already argued that one cannot judge a performance in any given field (politics, medicine, investments, ETEs) by the results. Now we’ll introduce the other factor that is the costs of the alternative. What if history played out differently and you made more than you expected (or less, for that matter). The other branches that could have happened after the initial event or decision. Such substitute courses of events are what we will call alternative histories.

Consider two guys in New York, Bob and John. Bob is a janitor who recently got lucky, won the New Jersey lottery, and moved to a wealthy neighborhood. John, his next-door neighbor, is of more modest condition who has been drilling teeth eight hours a day over the past thirty-five years. Now comes the trick, thanks to the dullness of the career path that he chose; if John had to relive his life a few thousand times since graduation from dental school, the range of possible outcomes would be relatively narrow. He would choose some dental school and complete his education in one way or the other. At best, he would end up drilling the rich teeth of the New York Park Avenue residents, while the worst would show him drilling teeth in some small town and in summer camps. Furthermore, assuming he graduated from a very prestigious teeth drilling school, the range of outcomes would be even more compressed.

Whereas Bob, the janitor who loves gambling, if he had to relive his life a million times, almost all of them would see him performing gambling activities (and spending endless dollars on fruitless lottery tickets), and one in a million would see him winning the New Jersey lottery.

John can be said to be extremely rich on the average of lives he could have led—he takes so little risk in his career that there could have been very few disastrous outcomes. If he were to relive his professional life a few million times, very few sample paths would be marred by bad luck—but, owing to his conservatism, very few as well would be affected by extreme good fortune. Therefore, he would be wealthy according to this unusual (and probabilistic) method of accounting for wealth.

For most people, the probability is about what may happen in the future, not events in the observed past. An event that has already taken place has 100% probability, i.e., certainty. What we need to agree on to use this probabilistic method is that although these events have happened, the outcome isn’t free of all the realities that could have happened.

We often hear from politicians or “motivational speakers” that “I followed the best course.” And like many platitudes, this one, while being too obvious, is not easy to carry out in practice.

Russian Roulette

I would like to illustrate the strange concept of alternative histories by this thought experiment. Imagine an eccentric (and bored) billionaire offering you $10 million to play Russian roulette, which for the uninformed, is a game where you put a revolver containing one bullet in the six available chambers to your head and pull the trigger. Each realization would count as one history, and we have a total of six possible histories of equal probabilities. Luckily for the player, five out of these six histories would lead to enrichment; one would lead to an obituary with an embarrassing (but certainly original) cause of death. The problem is that only one of the histories is observed in reality. The winner of $10 million would elicit the admiration and praise of some fatuous journalist (the very same ones who unconditionally admire the Forbes 500 billionaires). The public observes the external signs of wealth without even having a glimpse at the source. We will call such sources the generators.

Consider the possibility that this Russian roulette winner would be used as a role model by his family, friends, and neighbors. Although the remaining five histories are not observable, one should be able to guess their attributes. It requires some thoughtfulness and personal courage. Furthermore, in time, if the roulette-betting fool keeps playing the game, the bad histories will tend to catch up with him. Thus, if a twenty-five-year-old played Russian roulette, say, once a year, there would be a very slim possibility of his surviving until his fiftieth birthday—but, if there are enough players, say thousands of twenty-five-year-old players, we can expect to see a handful of (very rich) survivors (and a large and embarrassing cemetery).

This also presents a dilemma: $10 million earned through Russian roulette does not have the same value as $10 million earned through diligent and artful dentistry practice. They are the same, can buy the same goods, except that one’s dependence on randomness is greater than the other. To an accountant, though, they would be identical; to your next-door neighbor too. Yet, deep down, one can consider them as qualitatively different.

Arguably, in expectation, a dentist is considerably more affluent than the rock musician who is driven in a pink Rolls Royce, the speculator who bids up the price of impressionist paintings, or the entrepreneur who collects private jets. One cannot consider a profession without considering the average of the people who enter it, not the sample of those who have succeeded in it.

An Even More Vicious Roulette

Reality is far more vicious than our Russian roulette experiment. First, it delivers the fatal bullet relatively infrequently, like if the revolver would have had hundreds, even thousands, of chambers instead of six. After a few tries, one forgets about the existence of a bullet under a numbing false sense of security. This is what we can call a black swan problem. An improbable event is so drastic that it seems almost impossible, yet its consequences are too high to bear. It is also related to a problem called the denigration of history. Gamblers, investors, and decision-makers feel that the sorts of things that happen to others would not necessarily happen to them.

Second, unlike a game like Russian roulette which has well-defined rules, where the risks are visible to anyone capable of multiplying and dividing by six, one does not observe the barrel of reality. Very rarely is the generator visible to the naked eye. Thus, one can unwittingly play Russian roulette and call it by some alternative “low risk” name. We see the wealth being generated, never the processor, which makes people lose sight of their risks, and never consider the losers, leading to survivorship bias. The game seems terribly easy, and we play along carelessly. Even scientists with all their sophistication in calculating probabilities cannot deliver any meaningful answer about the odds since knowledge of these depends on our witnessing the barrel of reality—of which we generally know nothing.

Finally, there is this human factor to this. There is ingratitude in warning people about something abstract (by definition, anything that did not happen is abstract). Say you are in the business of selling insurances. You try to protect investors from potentially rare events by constructing instruments that shield them from their sting. Say that nothing happens during the period. Some investors will complain about your just spending their money; some will even try to make you feel sorry, They’ll say that you wasted their money on insurance last year but since their factory did not burn, it was a stupid expense. They’ll foolishly advise you that you should only insure for events that happen. But the world is not that homogeneous: There are some (though very few) who will call you to express their gratitude and thank you for having protected them from the events that did not take place.

The degree of resistance to randomness in one’s life is an abstract idea, part of its logic counterintuitive, and, to confuse matters, its realizations non-observable. Clearly, this way of judging matters is probabilistic in nature; it relies on the notion of what could have probably happened and requires a certain mental attitude with respect to one’s observations. Overall, history is potent enough to deliver on time in the medium to long run.